05/10/2023 – Why Was Exodus Written?

If you normally tune in to this channel for interreligious related info, or the thought of important thinkers like Paul Tillich, I’m so happy you’re here and support this channel. We’re going to have a summer series on Tillich and also cycle back to some interreligious themes as well after that, but today we’ve got a really interesting episode on what the Exodus narrative in ancient Judaism is really about. If all stories are interpretations of the what the storyteller finds important, why was the Exodus account written? There’s so much symbolism going on here. You’re really going to like this one. Believe me, it’s an eye-opener. Check this out. This is TenOnReligion.

Hey peeps, it’s Dr. B. with TenOnReligion. If you like religion and philosophy content one thing I really need you to do is to smash that sub button because it really helps out the channel. The transcript is available at TenOnReligion.com and new episodes are posted every two weeks, at noon, U.S. Pacific time, so drop me some views.

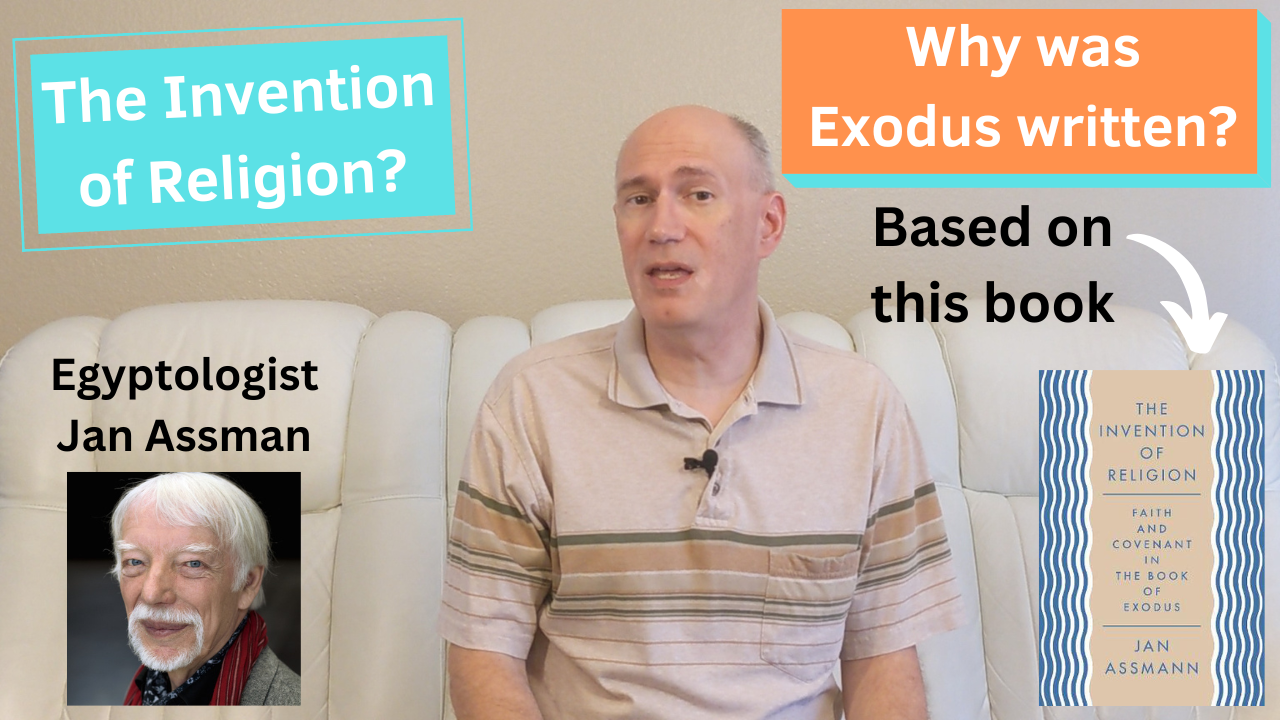

Every once in a while, I really get into the history of religion. I’ve read a lot of books about the history of religion, mostly on Judaism and Christianity, but I’ve also delved into the history of Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism and a few others. I recently read a book I’ve wanted to read ever since it came out in 2018, titled The Invention of Religion: Faith and Covenant in the Book of Exodus. The reason why I’ve wanted to read it is that it’s written by a famous German Egyptologist named Jan Assman and thus it presents more of a historical and balanced view. I’m going to mention the basic structure of the book and then try to highlight why the Exodus account in the Bible was written, and thus, how religion was “invented.” Let’s get started.

First off, while you’re watching this, think about why the author titles this book The Invention of Religion. I’ll come back and ask you later. The book has three main parts. Part one is on general foundations such as how the book of Exodus is structured and some historical background. Part two is on the content of the Exodus narrative, and part three covers the covenant and its institutionalization. The main theological themes present in the narrative are the ideas that, one, Israel has overcome Egypt as the supreme power and influence in the area, and two, has to leave Babylon to overcome the exile experience from the years 586-516 – a period of 70 years. The two main components of the narrative are the Exodus tradition and the desert-wandering tradition, which may have had separate influences and then at some point later in time brought together into a single account.

There are ten chapters in this book and we don’t have time to talk about all of them, but let’s highlight some important sections. The book starts out by mentioning how God is revealed through six steps: God’s name, God’s power, the covenant, the tabernacle, the divine being, and the institutionalized divine presence. This is really interesting, but what is even better is the historical background which inspired the writing of the narrative. There’s a great chart comparing the events in the narrative itself with what is actually going on when the narrative is being composed. For example, the narrative first centers on Egyptian oppression, freedom from slavery, and the departure of the children of Israel (thus the Exodus, or “exiting” from all this negativity). The time this was narrated though, was after the Assyrian and Babylonian oppression, the fall and destruction of Jerusalem, and the deportation of the elite in society to Babylon. The revelation of the law and covenant at Sinai and the building of the Tabernacle was narrated during the 70 years in exile. The wandering in the desert for 40 years as punishment of the guilty generation is a metaphor for the return under Persian rule, with the “sins of the fathers” as a metaphor both for those who were responsible for the downfall of Jerusalem as well as the resistance of those who stayed behind – specifically those who integrated in Babylon and resisted the demand to return to a devasted Jerusalem. Lastly, the occupation of Canaan is the rebuilding of the Temple, renewal of the covenant, and reestablishment of Israel as a concept in the form of Judaism. The Persian province was called Yehud, and its people, the Yehudim, which is likely where the word “Judaism” came from – the religious and cultural practices of the people of Yehud.

So, some quick background here. The real nation of Israel back in the day was ten times larger than the much smaller nation of Judah to the south. When Israel became a vassal of the bigger Assyrian Empire, and ultimately didn’t play nice, Assyria invaded and took the leadership and some of the upper class into exile. Many others fled south as refugees into Judah and so there was this huge population surge. The ones who didn’t flee south into Judah remained in the northern country. In Judah, a YHWH-alone group became dominant in the 700’s with the focus on the worship of YHWH and Jerusalem-centered practices. Later, after the Babylonian exiles slowly returned, they wanted to use the name Israel because it was the better name since it was historically the larger and more powerful nation of the two. They invited the people in the north to join them. Some did, but others didn’t. So now there are two groups of people – those in the south living under the concept of Israel, and those in the north living in the real nation of Israel. But the south grew more populous and so now the winners are writing the story. The “Canaanites” wiped out in the conquest after the Exodus refers to religious practices before the exile or those who were practicing Babylonian religion – basically everything that wasn’t “YHWH-alone.” Did you get all that?

The Exodus represents not just a story retold, but retold anew in light of the present cultural context. Canaan stands for idolatry as seen in the first five of the Ten Commandments, and Egypt and stands for oppression as seen in the second five. The Exodus story is not to be found in any sort of archeological verification, but in its significance for the storyteller. All stories are interpretations of the what the storyteller finds important. In Egypt the king was seen as the son of deity and in Mesopotamia as groom of deity, but now these metaphors are the people instead. A particular god YHWH calls a particular people Israel so that they can acquire the status of a divine people. The purpose is to create a cultural and religious identity as a new foundation after the Babylonian exile. In ancient vassal treaties an animal was cut in two, or sacrificed, and one part was given to each party. Thus, in the narrative the covenant with YHWH included yearly sacrificial animals with half of the blood sprinkled on the altar in the Tabernacle and the other half on the people. Why is this important? In Egypt, the gods created no laws but expected the king to carry out this task. When the exiles returned to Judah to rebuild the Temple, the covenant code acquires a framework. This becomes God’s law which is everlasting as opposed to the laws of a monarch which die when the monarch dies. That’s why the ten plagues in the narrative represent the symbolic battle between YHWH and the gods of Egypt.

Where does that leave us? What’s the takeaway here? The hypothetical origins of the Exodus story are less important than the historical conditions of its literary creation which provides those telling the story with an identity. In short, the Exodus is an act of crossing from old to new. A transition from a state to a people. This is still celebrated today in the Passover meal in which each member of the family takes part in reciting in the first person along with representational foods for each component of the narrative. See, aren’t the best stories always told when sharing a meal?

So, what do you think about the development of the Exodus narrative? Were you aware that the Exodus account represents a story retold in light of Judah’s then-present historical and cultural context? Why do you think the author titled this book, The Invention of Religion? Leave a comment below and let me know what you think. Until next time, stay curious. If you enjoyed this, support the channel in the link below, please like and share this video and subscribe to this channel. This is TenOnReligion.

Jan Assman. The Invention of Religion: Faith and Covenant in the Book of Exodus. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2018.